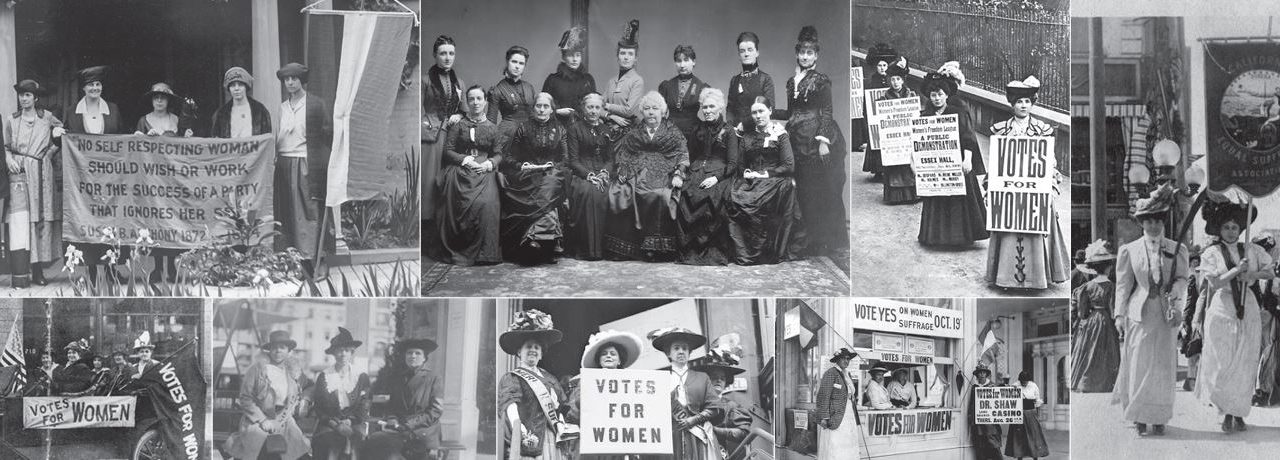

1920-2020 Centennial Anniversary of the United States Constitution’s 19th Amendment Giving Women the Right to Vote

By Hayley Mattson and Megan Olshefski

Today, August 18 marks the centennial anniversary of the United States Constitution’s 19th Amendment’s ratification. The 19th Amendment enfranchised all American women and declared for the first time that they, like men, deserve all the rights and responsibilities of citizenship.

After the founding of the United States in 1776, the thirteen states were left to decide separately upon their voting rights. This resulted in state-by-state requirements based on gender, religion, race, tax bracket, and property ownership. Initially, New Jersey’s 1776 constitution permitted “all inhabitants” (including women) the right to vote; but an 1807 law ensured the end of women’s attendance at the polls. Interestingly though women, even though they could not vote, could run for office.

During this time, several reform groups started multiplying across the United States, temperance leagues, religious movements, moral-reform societies, anti-slavery organizations, and in many of these, women played a prominent role.

This lead to many American women to began rebelling against the “Cult of True Womanhood,” that is, the idea that the only “true” woman was a virtuous, obedient wife and mother concerned exclusively with home family. In turn, this contributed to a new way of thinking about what it meant to be a woman and a citizen of the United States.

As the years went on and women sought to pass reform legislation, the drive to change society intensified. In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Martha Wright, Mary Ann M’Clintock, and Jane Hunt issued a call for a women’s rights conference at Seneca Falls, New York, where Stanton lived. Prior to the event, Stanton drafted the “Declaration of Sentiments and Grievances,” which she modeled after the Declaration of Independence. The declaration began with “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights…” she continued to lay out the present injustices against women in the United States. The declaration then called for women to be viewed as full citizens, and granted the same civil, economic, and political rights as men.

The convention sparked a national movement that lasted seven decades. During the 1850s, the women’s rights movement gathered steam but then lost momentum when the Civil War began. Almost immediately after the war ended, the 14th and the 15th Amendments to the Constitution raised familiar questions of suffrage and citizenship.

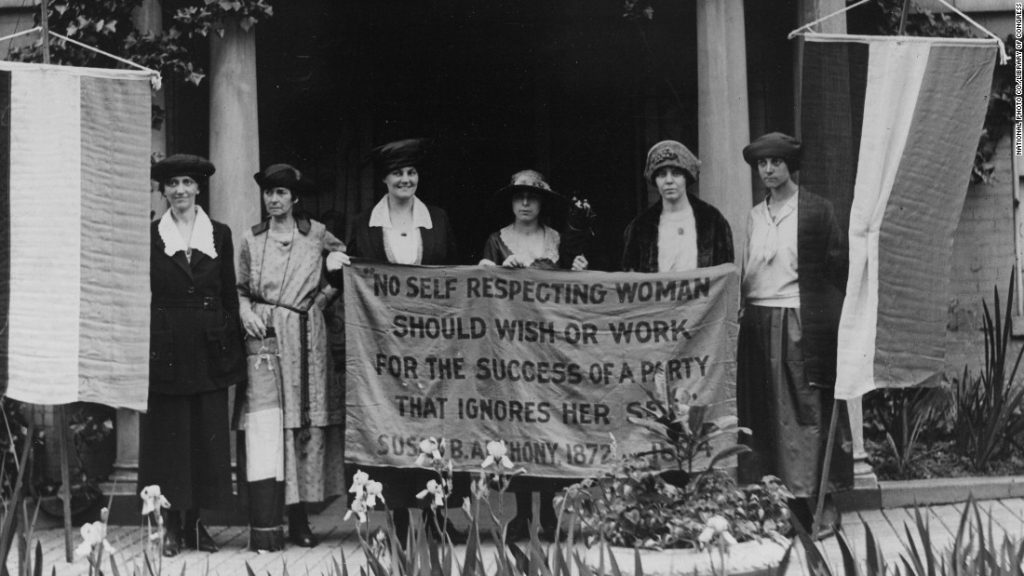

The ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868 extended the Constitution’s protection to all citizens and defined “citizens” as “male.” In 1869, the “National Woman Suffrage Association” (NWSA) was formed by Stanton and Susan B. Anthony to focus efforts on a federal constitutional amendment that would grant women the right to vote.

A year later, in 1870, the 15th Amendment guaranteed African American men the right to vote. Declaring that “the right of citizens … to vote shall not be denied or abridged … on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” the amendment still excluded women. Even after Stanton and Anthony, along with other activists, fought to have all women included, regardless of race, women were still denied that right.

As a result, some women’s suffrage organizations refused to support the 15th Amendment. This led to the argument that it was not right to jeopardize African American men’s right to vote by tying to the evidently less popular campaign for female suffrage.

During that time, a pro-15th Amendment group formed called the “American Woman Suffrage Association” (AWSA) founded by abolitionists Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell. The group supported the 15th Amendment and feared it would not pass if it included voting rights for women.

This hostility between the two organizations eventually faded, and in 1890 the two groups merged to form the “National American Woman Suffrage Association.” Stanton was the organization’s first president.

Both Stanton and Anthony played a fundamental role in the women’s suffrage movement. They both were pioneers who led future women activists, and both died before seeing their hard work come to fruition. The 19th Amendment was later known as the “Susan B. Anthony Amendment” to honor her work on behalf of women’s rights.

Over time, the suffragists’ approach had evolved. Instead of arguing that women deserved the same rights and responsibilities as men because women and men were “created equal,” the new generation of activists argued that women deserved the vote because they were different from men. This direction deemed their domesticity as a political virtue, using that to create a purer, more moral “maternal commonwealth.”

After countless efforts, on August 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified after passing both Congress’s houses and winning approval from the thirty-six states necessary for a two-thirds majority. The long-awaited victory granted women the right to vote; and, in doing so, proclaimed to the entire country that like men, they deserved all of the rights that come with citizenship.

On November 2 of that year, after almost a century of protest, more than 8 million women across the United States voted for the first time. Today more than 68 million women vote in elections.

Change and progress are possible when we stand up against injustices through organization, determination, and bravery. One hundred years after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, we honor our history and the sacrifices countless women and men made to acquire women’s rights. By voting, we not only honor them, but we determine the world we leave our future generations.

Publisher’s Note: In honor of the centennial over the next few months leading to the 2020 elections, we will be writing a series of our history’s voting rights and sharing the brave and courageous individuals that fought for equality and for their voices to be heard. To read the full version of this article, please see the August issue of Paso Robles Magazine and Colony Magazine.

References for this article were history.com, womensvote100.org, 2020centennial.org, and biography.org.